Vesicoureteral reflux is the abnormal backflow of urine from the bladder to the ureter and/or kidney. When the affected individual voids, the urinary bladder contracts. The urine is supposed to leave through the urethra, but if the vesicoureteral junction is abnormal some urine will be forced back up into the ureter. How bad is the junction? How much urine goes up rather than down? These are the questions that determine the grading of reflux, established by the International Reflux Grading system.

- Grade I - Urine backs up into the ureter only. It does not reach the kidney, which therefore remains normal.

- Grade II - Urine backs up into the ureter and reaches the renal pelvis and calyces. However, there isn't enough pressure to actually change the form of the calyces, so the kidney still looks normal.

- Grade III - More urine can go up with a little higher pressure. The calyces beging to dilate and are said to be mildly blunted.

- Grade IV - A lot of urine can go up, with considerable pressure. The calyces are moderately blunted, and the renal pelvis is moderately dilated.

- Grade V - The kidney is badly affected by all that urine backing up - the renal pelvis is severely dilated, the calyses are very malformed and severely blunted.

So what makes a vesicoureteral junction not function properly?

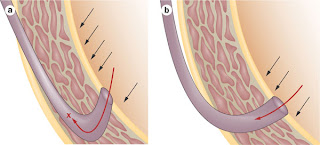

Let's understand the normal junction first. The ureter enters the urinary bladder by traversing the bladder wall. It enters obliquely, so there is a larger portion of the ureter that is inside the muscular wall of the bladder - the intramural tunnel. When the bladder contracts during voiding, pressure is exerted along the entire length of the intramural tunnel and prevents urine from backing up. If the implantation of the ureter is such that the intramural tunnel is shorter, there is less tunnel available to prevent the backup. Hence, primary reflux results from a short intramural tunnel.

There are other causes of reflux:

There are other causes of reflux:- Bladder outlet obstruction - increases the bladder pressure and forces urine back up.

- Detrusor instability

- Duplicated collecting system - but this is basically an extension of the short intramural tunnel. The duplicated ureter often implants abnormally and has a short intramural tunnel!

- Paraureteral diverticulum

If still untreated, renal scarring will progress to hypertension and end-stage renal disease. The latter is predicted by proteinuria (>1 g/day) and is the result of the development of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis and interstitial scarring. Early diagnosis is desired in order to prevent this acquired renal damage.

Understanding the pathophysiology helps determine the significance of the follow-up necessary for these patients. Infants should not get urinary tract infections. In general, UTI in infants and children serve as a marker for abnormalities of the urinary tract. After infancy, normal girls have a somewhat higher incidence of UTIs (even with a normal genitourinary tract) so they can "get away" with one UTI before the physician freaks out. This determines the criteria for work-up to rule out reflux. The test of choice here is a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). Indications are:

- All infants younger than one year of age after their first episode of UTI. The rate of reflux among children younger than 1 year of age with UTI exceeds 50%.

- All boys, regardless of age, after their first UTI

- Girls after their second UTI

During follow-up if a patient with mild reflux who is compliant with prophylactic antibiotics develops a UTI, this may tip the patient towards surgical intervention.

The prophylactic antibiotic of choice is trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or nitrofurantoin.

No comments:

Post a Comment